Dear Seniors,

Welcome to your last high school class. Ever. Welcome to a new kind of school life, where you will have much more choice about where to go and what to do. In minutes, your classes will all be done; you’ll have time on your hands to study, take tests, and most importantly, to attend to the things and people you care about the most. You’re about to mark a significant milestone in life: high school graduation. Somewhere or another, you’ve been getting up and going to school for the past twelve or thirteen or fourteen or more years. In three weeks, this part of your life will be done.

But as Douglas Adams said, “Don’t panic.” Graduation will be a little bit like turning 10 (first birthday in double digits) or 18 (adulthood, whatever that means). For me, all these milestones were just markers passed on the road of life. The road rarely changes at the mile markers; you just pass ‘em. That’s not to say your life won’t change — it surely will — but the changes happen at their own unpredictable pace. In fact, it happens so strangely that some of us get caught by surprise, like Billy Pilgrim’s mother, who, in her hospital room, encounters a brief moment of lucidity, stares Billy in the eye and asks him, “How did I get so old?” When I was about to go to college, my dad said to me, “Bill, you’ll be amazed how fast the time goes between freshman week… and your 25th reunion.” I went to that reunion a couple of years ago. The old man was right.

Over the next three weeks, you may find yourself thinking about how eager you are for something to be over — your last test, your last day of school, graduation. I’d invite you to resist those thoughts, however. The phrase “Don’t wish your life away” comes to mind. And herein we have an opportunity to look at what some of the authors we’ve read over the past 20 months have said about the subject. Vonnegut gave us Billy Pilgrim, who, by

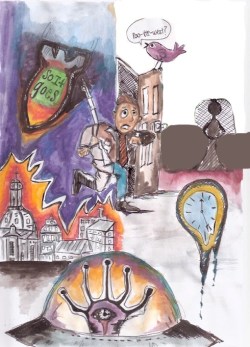

Anna Stenning: Slaughterhouse-Five Images

giving up on himself, discovered the “good news” that time doesn’t matter and life is meaningless. Knowing he’ll repeat moments and relive his life in a continuous, spastic series of disjointed moments, he says, “Hello, goodbye, hello, goodbye, hello…” which he found comforting, but we readers can see as problematic. An infinite, meaningless existence is not for most of us.

Becket, of course, gives us two antiheroes who share a lot in common with Billy, in their own absurd way. Sadly, Didi and Gogo don’t have the thrill of being kidnapped by space aliens. They just unconsciously have slipped into a life — immeasurably long — of waiting for something. When you find yourself killing time as you wait for that next thing to happen, or to be over, remember what happens (sorry — what doesn’t happen) to our friends who wait for Godot. Didi understands that all this… existence… won’t last forever. In fact, he sees life as infinitely short. He says he’s “born astride a grave,” delivered into existence by “the grave digger,” who waits six feet below with forceps.  Didi’s aware that “in an instant all will vanish and we’ll be alone once more, in the midst of nothingness!” And yet, he can’t find a way to break out of his life of waiting. By the way, for many of the sorrier characters whose lives we’ve explored, this idea of being alone goes hand in hand with have a meaningless life. I’ve got a theory on that…

Didi’s aware that “in an instant all will vanish and we’ll be alone once more, in the midst of nothingness!” And yet, he can’t find a way to break out of his life of waiting. By the way, for many of the sorrier characters whose lives we’ve explored, this idea of being alone goes hand in hand with have a meaningless life. I’ve got a theory on that…

At a less abstract level, Willy Loman shows us what happens when you wrap all your life’s ambition into an unachievable, distant goal. Willy dreams of recognition, of being “well-liked” by masses of people, or at least of being the father Biff Loman, a well-liked man. Tragically, he can’t accept the love of his wife or that of his sons, or his friend Charlie — and so even after achieving (by the skin of his teeth) the American dream of owning a house and having a family, he gives it all up for the illusory promise of wealth — and maybe some celebrity — for his son. The other option, of course, is to pass through life being completely disinterested in creating any sort of meaning — in being earnest in anything but name. Oscar Wilde’s lessons, I think, provide a challenge equal to Beckett’s and Miller’s, and I’m grateful for the laughs he provides along the way.

If you’re starting to feel like this last lecture is a review of the course, well, OK, you caught me. Indulge me for another paragraph: All the authors we have read over the past years had two things in common:

- They all write beautiful and entertaining literature

- They all challenge us to be better human beings

Thanks Ana Stenning for these images from The Wind Up Bird Chronicles!

Murakami shows us that life can be filled with confusion and uncertainty, and he also shows us that when things appear to be at rock bottom, we can always go down a well and get stuck… And we can open our eyes to possibilities and reach out to discover more. We can fight the monsters we need to fight and construct the connections we long to make. William Blake’s poems demand that we look at the world through the eyes of both innocent, suffering children and “woke,” angry adults. He throws up the beauty and the ugliness of life and demands that we see it — even in places we do not want to. The tragic stories of Gatsby, the man who (like Willy Loman) wished only to be “well-liked” by a certain class of people who never would let him in, and to be loved by a woman incapable of loving anyone — and who (a little like Billy Pilgrim) insisted that you can repeat the past — and Grenouille, the boy who grows up impervious to disease and immune to the all of the foulest things people are capable of (ignorance, hatred, greed, self-absorption, mob violence) and is ultimately incapable of showing the only thing that really matters in life: love — both challenge us to live beyond the bad things we inevitably encounter.

In both of the Shakespearean comedies, family interests and human pettiness get in the way of true, natural love, and nearly result in the useless deaths of romantic heroines. Hero feigns her death, and unlike Juliet, she gets marry the man she loves — even though he’s treated her horribly. Hermia defies her father’s death threat, runs into a dangerous wilderness, and survives the vagaries of that forest — and the horrible treatment of the man she loves — but gets to marry her guy in the end, too. The thing about all three comedies, though, is the temporary nature of this happiness. Do things work out in the long run for Jack and Gwendolyn, Algy and Cecily? For Hero and Claudio? Beatrice and Benedick? For Hermia and Lysander, Helena and Demetrius? For Theseus and Hippolyta? Oberon and Titania? We’ll never know.

In both of the Shakespearean comedies, family interests and human pettiness get in the way of true, natural love, and nearly result in the useless deaths of romantic heroines. Hero feigns her death, and unlike Juliet, she gets marry the man she loves — even though he’s treated her horribly. Hermia defies her father’s death threat, runs into a dangerous wilderness, and survives the vagaries of that forest — and the horrible treatment of the man she loves — but gets to marry her guy in the end, too. The thing about all three comedies, though, is the temporary nature of this happiness. Do things work out in the long run for Jack and Gwendolyn, Algy and Cecily? For Hero and Claudio? Beatrice and Benedick? For Hermia and Lysander, Helena and Demetrius? For Theseus and Hippolyta? Oberon and Titania? We’ll never know.

And you

will never

know

either.

For them,

or for you.

I’m hopeful that your lives will be comedies: we keep going, we do crazy things, we survive, we act, and at times, things seem to work out OK. And we keep on keepin’ on while passing these happy (and sad) milestones.

On a personal note, I’ve passed a few of these recently; somewhere in February I completed my 25th year marker in professional education. Two years ago, in June, I went to my 25th college reunion. Next December I turn 50. Like graduation, these three arbitrary markers offer a chance to look back at what we’ve learned along the way. They may be relevant in this context because (believe it or not) you’ll be starting your second 25 years and beginning your work lives pretty soon. So what have I learned? Most of all, I’ve found that there’s much more learning to do. To illustrate:

- When I graduated from high school, I thought I was a musician. Thirty years later, I can hear more and play more than I possibly could have imagined back then. And there’s vast room for growth.

- When I graduated from high school, I thought I was athletic. But I had no idea of the commitment and discipline athletes have, until this very year, when I attempted to race with cyclists up and down Mt. Kenya. Now I’m much fitter, faster, and stronger than I was back then. And I have a new goal: To complete that race next year — when I’m fifty.

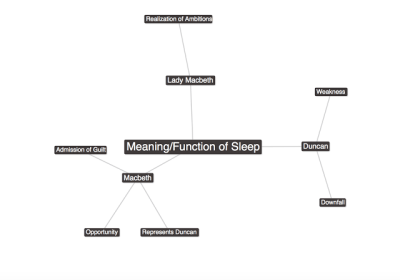

- When I graduated from high school, I thought I knew a lot — about everything. Now I see enormous possibilities to know more. Thirty years later I’ve been lucky enough to live in four new countries and learn three new languages. I’ve taught a hundred different novels and plays, and read hundreds of poems from authors I’d never heard of in high school or college. With Shakespeare, I hadn’t read and understood a single play until I taught Macbeth for the first time. Since then I’ve prepared units for and taught 9 of his plays and studied a few more. I’ve studied at the Folger Shakespeare Library and at the Globe Theatre. The good luck of living these experiences has shown me the wealth of knowledge and learning that lies ahead. You can learn a lot in 25 years; I hope to learn much more in the next 25.

For most of you, we’ve been gathering to learn about and from literature for the better part of two years. And now, for better or for worse, we’ve reached the last minute or so of our official time together.

As you walk out that door over there, know that this class has been memorable and wonderful. You’ve been a dream of a class: a curious, interested group of voracious readers. You’ve challenged me to think and rethink my ideas on these works of literature. You’ve stretched your ideas and worked and re-worked your writing. It’s been a joy to watch you perform, to revise over…and over…and over… your essays, and to share your two-year life journey with me in some small way. It might seem small, but I’ll always remember being invited me to take a class picture with you at the prom. You’ve inspired me by doing things you love: by reading and sharing your ideas with each other, by making beautiful art, by writing plays, by playing music, by playing sports, by performing theater, and by sharing kindness. Know that all these things have lifted up the world a little bit. You’re bringing us a little closer to the “world without collisions” that Sam envisions for the future. Remember Sam’s lesson: He endures humiliation after humiliation, and even in the worst moment, he finds it inside himself to seek a better world — and to invite Hally (and the rest of us) to be a better human being. You’ve bolstered this middle aged teacher’s faith in the future. As long as you and people like you keep on doing what you’re doing, we’ll be alright.

Have a great life.

BP

April 2018

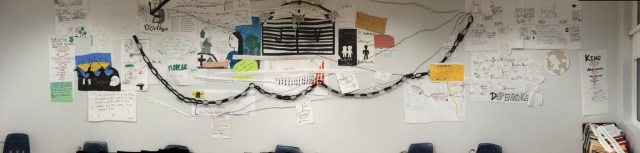

Now, however, we are here, in this space, for your last class, entering the season of lasts. I like that word, “last” with all its ambiguity. I hope I’ve lasted this far without boring you, and I hope some of the works we’ve read leave a lasting impression. Looking at our classroom the walls, I hope making these collages of words have left words and ideas that last in your literary memory.

Now, however, we are here, in this space, for your last class, entering the season of lasts. I like that word, “last” with all its ambiguity. I hope I’ve lasted this far without boring you, and I hope some of the works we’ve read leave a lasting impression. Looking at our classroom the walls, I hope making these collages of words have left words and ideas that last in your literary memory.